Deconstructing the Marketing Competition – Part 1

|

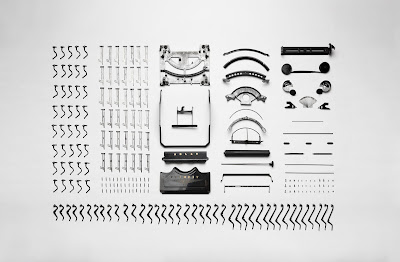

| Photo by Florian Klauer on Unsplash |

But this obsessive need to be perfect sparks from our innate instinct of curiosity.

Human beings as a species are the best problem solvers on earth. This is because of our instinct to satisfy our insatiable curiosity. Our brains are hardwired for it. We are, in fact, obsessed with exploring, knowing things, needing information and solving mysteries. It is this primal instinct that has enabled us to thrive as the dominant species on the planet. Simply put, we are informavores.

Today the concept of deconstruction has been successfully adapted in many fields and famously in artworks like sculptures and food like pies, samosas, tiramisus and so on.

Curiosity starts early from childhood. One of the ways we satiate this need is by taking things apart. Basically deconstructing objects and items to see what’s inside, how it works and putting them back together again.

Most of us have taken things apart ourselves just to see what’s inside them. And also put them back together. Some successfully, others not so much. Some of our famous subjects are spring pens, cassette tapes, dial phones, iron boxes, and alarm clocks.

I remember sneaking into the toolbox to borrow a screwdriver and taking apart pens and cassette just to know what’s inside, have a look-see and put them back together. I was successful with the pens and the cassette but no so much with the iron box. I have taken apart a few of my toys and martyred a few in my quest for knowledge. As a teenager, I opened the cabinet box of my CPU to see what’s inside. I decided it was too advanced to explore through deconstruction and also, it was not worth the trouble I’d get in. So I screwed the box back on once I saw how things work.

Deconstruction, as it turns out, is a popular method for teaching in schools. We have broken down math problems & theories to understand concepts, history into chronological events, sentences to understand the grammar. People have made a profession out of it too. The local garages with their talented mechanics, small electronic repair shops, tailors, and many many more creative professionals.

So what does this have to do with marketing and competition?

As a marketer, one of our many responsibilities lies in knowing what our competition is up to, both creatively & strategically. And we must be on our toes as the market, trends, customer preferences can change very quickly and dramatically.

We collect information like everyone else through:

- Scouring the internet for what our competitors are doing

- Talking to agencies, vendors, customers about what’s happening in the market and the competitors

- Collecting information first hand by either becoming or posing as a customer of our competitors

- Very expensive third-party research

And what we mostly do with this information is dump it together in a file or a folder, convert the data into numbers, and process it in a software or excel sheet basis a predefined method of the firm we are with. There are cases where we just get overwhelmed rendering our entire effort useless.

But there is a method to this madness that we call competitor analysis.

We do this in the hopes to decipher what they are up to and if we can match or one-up them in the game. We do this to have an edge, an advantage over the others.

Enter Deconstruction

One method that can be used to analyze competition is deconstruction.

You have a complete ad, a campaign, a strategy, a well thought out customer journey with you. You can selectively and systematically take apart each component of your study, examine how and why it makes your study whole. This approach can reveal the many secrets of your study and help you in formulating new ones too.

Using deconstruction would mean the selective and systematic dismantling of the components that make a whole in order to understand how a whole works. For this, one must understand how each part comes together and work in unison.

Imagine a retractable spring pen. When we click it, the nib emerges and the pen does its function of writing. But how does this contraption work? We can unscrew the pen, dismantle it and lay out its parts to understand what are their individual functions and how they relate to each other. Here’s a link to how a retractable spring pen works. On studying this someone came up with the idea of introducing multi-colored nibs and pen-pencils and so the innovations continue. The principal of this pen’s functionality was improved and adapted to various applications.

Let’s take the example of a print ad.

This can be dismantled as follows:

- Colour & Design - How does this attract attention?

- Language - What imagery comes to mind when reading this? What feelings does it invoke?

- Relationships - What inferences can be made with the images in the ad? And how do they relate to each other?

- Subtext - How many direct and indirect messages can one understand from the ad? And what is true and false in these messages?

- Accuracy - Are the facts of the ad accurate enough?

When the above parts are laid out and studied we could understand how the ad works as a whole unit and how each part of the ad contributes to it in unison.

As Aristotle puts it - The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

One can use similar dismantling techniques for the entire campaign, or even a media plan. The elements would, of course, differ but the basics remain the same.

But our job doesn’t end with just exposing the parts. We have to question its purpose as well. There is no limitation to the number of questions we can ask. But the idea of asking these questions will depend on the context of your objective for deconstruction. For example, if you want to know what kind of offer your competitors are highlighting, you can look for the ‘urgency’ components in the creative and question its relevance, priority, and purpose. Asking these questions will help you deeply understand your subject and guide you ahead.

What deconstruction helps you do is reveal the truth from the facts collected. And this truth is institutional to the subject being studied.

We have a lot of facts from the raw data collection process. And these facts can be inferred in ‘n’ number of combinations & permutations. The truth (or truths) in this case would be an assumption, a highly calculated guess. The probability of this being right can be high. But it remains an assumption. An illusory truth.

With deconstruction, the facts can be structured in a way to reveal the truth institutional to the subject and its intended purpose.

That's not all....Stay tuned for the sequel of 'Deconstruction'.

Comments

Post a Comment